Bombing flights in Russia

Event ID: 124

Categories:

01 July 1916

Source ID: 4

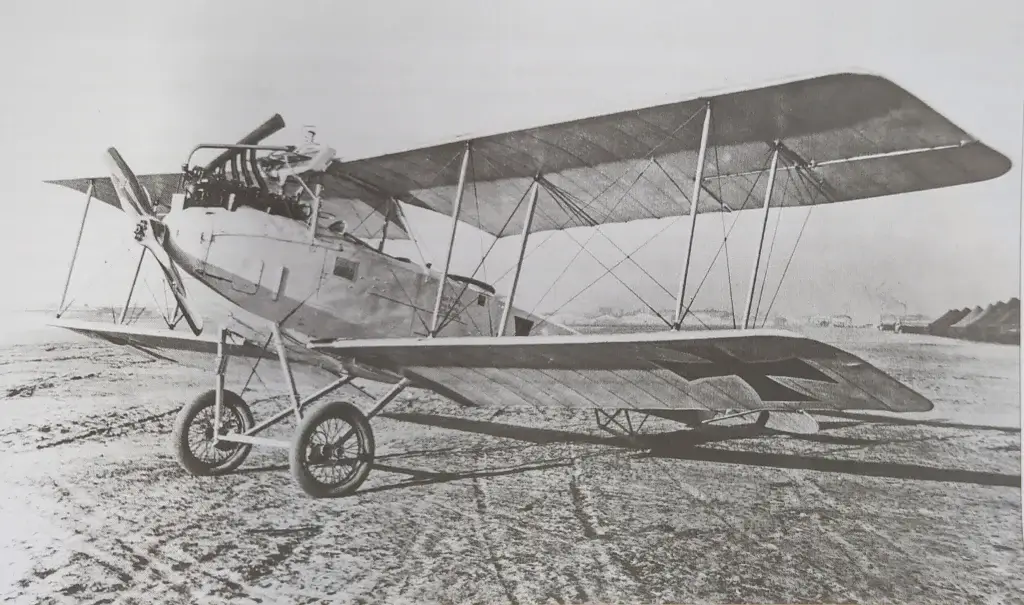

“Bombing flights in Russia. On the morning of 30 June we were suddenly told to load up. We didn’t know where we were going, but we had the right tip and were therefore not overly surprised when our commander surprised us with the news that we were going to Russia. We travelled all over Germany in our caravan train, consisting of dining and sleeping cars, and finally arrived in Kovel. There we stayed in our railway carriages. Of course, living in trains has a lot of advantages. You’re always ready to continue your journey and you always have the same accommodation. But in the Russian summer heat, a sleeping car is the most horrible thing there can be. That’s why I preferred to move to the nearby forest with two good friends, Gerstenberg and Scheele, where we pitched a tent and lived like gypsies. Those were good times. * In Russia, our fighter squadron dropped a lot of bombs. We kept ourselves busy annoying the Russians and laid our eggs on their most beautiful railway lines. On one of these days our whole squadron went out to bomb a very important railway station. It was called Manjewicze and was about thirty kilometres behind the front line, so not too far. The Russians had planned an attack and for this purpose the railway station was packed with trains. One train stood next to the other, a whole track was occupied by moving trains. You could see this very clearly from above; there was a transport train at every passing point. So it was a really worthwhile target for a bombing run. You can be enthusiastic about anything. That’s how I got enthusiastic about bombing for a while. I had a lot of fun paving over the brothers down there. I often went twice in one day. On this day we had set ourselves the target of Manjewicze. Each squadron headed for Russia as a unit. The planes were at the start, each pilot tried his engine again, because it is an embarrassing thing to make an emergency landing on the wrong party, especially in Russia. The Russians are crazy about aeroplanes. If he gets hold of one, he’s sure to kill him. That’s the only danger in Russia, because there are no enemy planes there, or hardly any at all. If one does come along, it will certainly have bad luck and be shot down. The balloon defence guns in Russia are sometimes quite good, but there are not enough of them. In any case, flying in the East is a recreation compared to the West. * The aircraft taxi heavily to the launch site. They are filled to their last load weight with bombs. I sometimes towed one hundred and fifty kilograms of bombs with a normal C-plane. I also had a heavy observer with me, which didn’t look like it was carrying any meat, and two machine guns ‘just in case’. I never got to try them out in Russia. It is a great pity that there is no Russian in my collection. Its cockade would certainly look very picturesque on the wall. A flight like that with a thick, heavily laden machine, especially in the Russian midday heat, is not to be taken lightly. The barges rock very unpleasantly. Of course they don’t fall down, the one hundred and fifty ‘horses’ make sure of that, but it’s not a pleasant feeling to have so much explosive charge and petrol with you. Finally you are in a calmer layer of air and gradually begin to enjoy the bombing flight. It’s nice to fly straight ahead, to have a specific target and a fixed mission. After dropping a bomb you have the feeling that you’ve achieved something, whereas sometimes on a fighter flight where you haven’t shot anyone down [84] you have to say to yourself: You could have done better. I really enjoyed dropping bombs. My observer had managed to fly over the target exactly vertically and, with the help of a telescopic sight, to catch the right moment to lay his egg. It is a beautiful flight to Manjewicze. I’ve done it several times. We passed over huge forest complexes, where the moose and lynx were certainly roaming. The villages also looked as if the foxes could say good night to each other. The only large village in the whole area was Manjewicze. There were countless tents pitched around the village and countless barracks at the railway station itself. We couldn’t recognise any red crosses. A squadron had been there before us. This could still be seen in individual smoking houses and barracks. They had not thrown badly. One exit of the station was obviously blocked by a hit. The locomotive was still steaming. Surely the drivers were somewhere in a shelter or something like that. On the other side, a locomotive was just pulling out at full speed. Of course, it was tempting to hit the thing. We flew at the thing and set a bomb a few hundred metres in front of it. The desired result was achieved, the locomotive stopped. We turn round and throw bomb after bomb, finely aimed through the telescopic sight, at the station. After all, we have time, nobody will bother us. An enemy airport is close by, but its pilots are nowhere to be seen. Defence guns only bang sporadically and in a completely different direction than we are flying. We save another bomb to use it to our advantage on the flight home. Then we see an enemy plane take off from his harbour. I wonder if he’s thinking of attacking us? I don’t think so. Rather, he is looking for safety in the air, because that is certainly the most convenient way to avoid personal danger to his life during bombing flights at airports. We make a few more detours and look for troop camps, because it’s great fun to worry the gentlemen down there with machine guns. Semi-savage tribes like the Asians are even more frightened than the educated English. It is particularly interesting to shoot at enemy cavalry. It causes tremendous unrest among the people. You suddenly see them dashing off in all directions. I wouldn’t like to be the squadron leader of a Cossack squadron that’s being machine-gunned [86] by airmen. Gradually we could see our lines again. Now it was time to get rid of our last bomb. We decided to bomb a tethered balloon, ‘the’ Russian tethered balloon. We were able to descend quite comfortably to a few hundred metres and throw a bomb at the captive balloon. At first it was pulled in with great haste, but as soon as the bomb had fallen, the pulling in stopped. I explained it to myself, not that I had hit it, but rather that the Russians had abandoned their hetman up there in the basket and had run away. We finally reached our front, our trenches, and when we got home we were a little surprised to find that we had been shot at from below, at least that’s what a hit in the wing showed. * On another occasion we were also in the same area and had been set up for an attack by the Russians, who intended to cross the Stochod. We arrived at the endangered spot, loaded with bombs and a lot of cartridges for the machine gun, and to our great surprise we saw how the Stochod was already being crossed by enemy cavalry. A single bridge served as a supply line. So it was clear: if you hit it, you could do the enemy a lot of damage. What’s more, large masses of troops were rolling across the narrow footbridge. We went down to the lowest possible height and could now clearly see that the enemy cavalry was marching across the crossing at great speed. The first bomb crashed not far from them, followed immediately by the second and third. A chaotic mess was created below. The bridge was not hit, but nevertheless the traffic had stopped completely and everything with legs had fled in all directions. The success was good, because there were only three bombs; the whole squadron followed. And so we were still able to achieve a lot. My observer shot firmly among the brothers with the machine gun and we had a lot of fun with it. Of course, I can’t say what our positive success was. The Russians didn’t tell me either. But I imagined that I had beaten off the Russian attack on my own. The Russian war chronicle will probably tell me after the war whether it’s true.”

Comments (0)